HOUSTON -- Julian Edelman was skeptical.

He was supposed to step into a tank with less than a foot of salty water warmed to the temperature of his skin, lay belly-up in the dark, and that was going to help him recover from the dozen or so jarring hits he takes on game days?

Sure. Okay, bub.

"When we got one, obviously I was a guy to make fun of it," Edelman said. "Then I started using it."

The Patriots introduced floatation therapy, or sensory-depravation therapy, to their players back in 2014. They now have two tanks sitting in tiled rooms at their Gillette Stadium facilities, and Edelman has come around.

An avid floater, the 30-year-old wideout popped in three or four times a week during the season. And he's far from the only one in the Patriots locker room who believes in the benefits of floating.

Tom Brady is a proponent and reportedly keeps a float tank of his own at home to help him remain atop his game as he nears 40. Chris Hogan has become a regular in the tanks this year after hearing Edelman and Brady rave about them. Matthew Slater has made floating for about an hour part of his weekly routine, and Dont'a Hightower has become so fond of it that he recently purchased passes for his mother and sister to float back in his home state of Tennessee.

Even when the Patriots moved their entire operation to the University of Houston and the JW Marriottin preparation for Super Bowl LI, players did their best to maintain their float schedules, just as they did two years ago before Super Bowl XLIX. The tanks are bulky and can contain 1,000 pounds of Epsom salt for buoyancy -- "It's like the Dead Sea," Edelman explained -- so they don't travel well. But there are at least five Houston-based businesses that offer floatation therapy, including three within a 15-minute drive from the team's hotel.

Patriot players frequented one of those spots during their stay, though they wouldn't say which, hoping to keep a low profile.

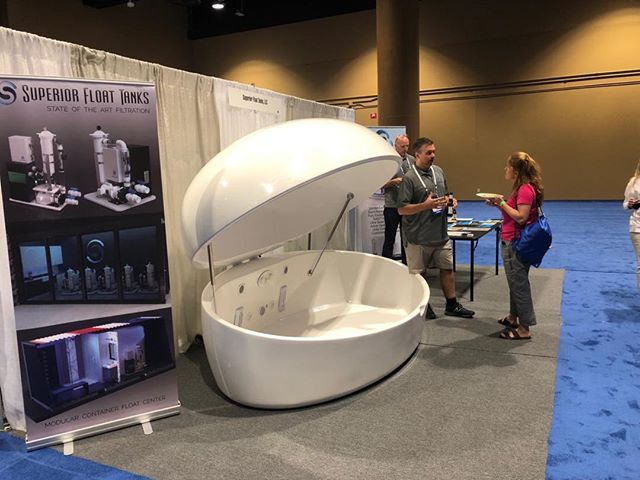

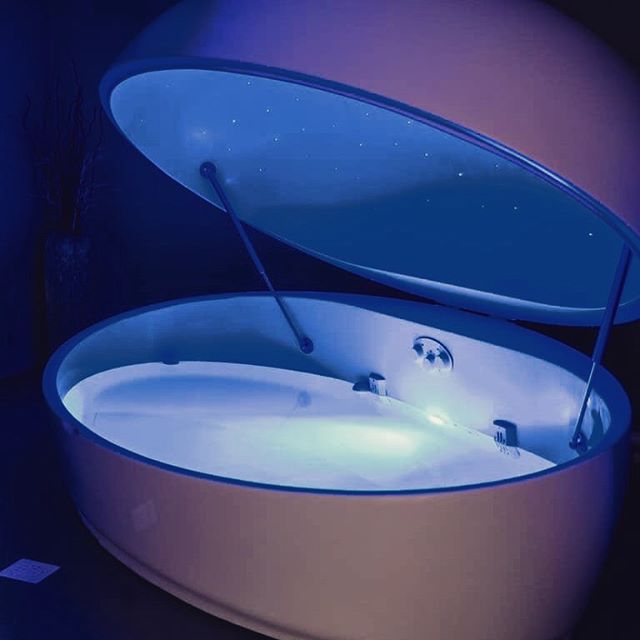

Despite the fact that they haven't been able to use the same tanks they've used all season, the basic elements of most sensory-depravation devices are the same: They're seven-to-eight feet long and three-to-four feet wide; they contain about 10-to-11 inches of water heated to about 94 degrees; they're covered to keep things dark; and they require enormous amounts of salt, allowing users to float effortlessly.

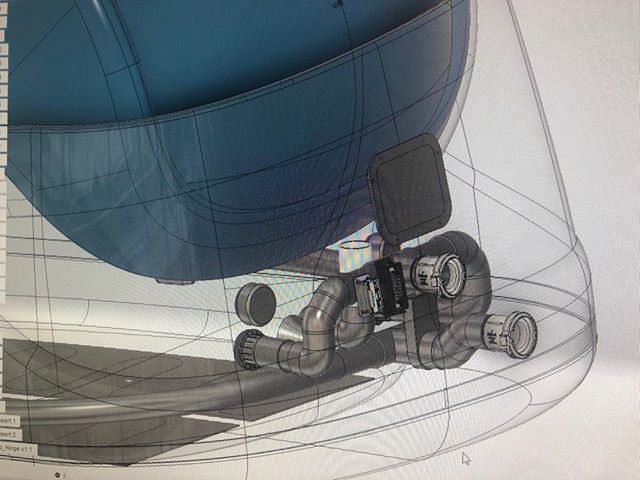

Some look like large metal coffins. Some have an oversized clamshell feel to them with a top that hinges open and closed, which is the type the Patriots use. Some look like futuristic sedans. But the experience in all of them is generally the same.

"You just lay back," Edelman said. "You gotta trust it. A lot of guys get anxiety for the first few times because your head doesn't go under. But once you get comfortable with it, it feels like you're just on a cloud or something because there're no pressure points. For athletes, I'm 120 percent all in on it."

'YOU GET TO JUST BE TOTALLY RELAXED'

Why, though, would a professional football player be interested in feeling like he's floating through space? How does that provide him an edge against his competition when he's either trying to hit someone or avoid being hit on Sundays?

Players inside the Patriots locker room say they believe the salt water helps reduce inflammation, and some like the idea of having a designated quiet space to think or pray.

But there's one primary benefit that they consistently highlight: Improved quality of sleep.

Many pass out inside the pods soon after they close themselves in because the combination of the darkness, the warmth, and the feeling of weightlessness make it an ideal environment for napping -- even better than sleeping in a cozy bed, where the body is still dealing with the effects of gravity, temperature, sound and light.

"It's not that often that you get to just be totally relaxed," Slater said. "Even when you're sleeping in bed, you're putting pressure on something. But when you get in there, you're really fully relaxed."

And when the nap is over, that's when some of the most critical effects kick in.

"The big thing it addresses is how you rest the night after you go in there," Slater said. "I think sleep is something that is totally underrated. As an athlete it's so important that you rest and recover your body, and I think it helps you do that at a higher level. The night after I get in that, I definitely rest a whole lot better."

"Once you get up and you shower and stuff," Hightower said, "you're usually really relaxed, like after a massage. I've got a big bean bag back at home, and as soon as I get back home, I'm putting on cartoons, I'm on the bean bag and passed out. That's pretty much my day after the float tank."

Hightower has used the tanks in previous seasons, but he said he's been in them more than ever this year. After making the Pro Bowl for the first time and putting himself in line to earn a sizable new contract as an impending free agent, he was reluctant to create too strong a link between his performance and the quality of his sleep, but he did admit, "It's been working for me this year so I'm going to keep going back to it."

"Especially putting in as much work as we do here, and guys who stay after and watch all the extra film, you want to get as much sleep as you can," Hightower continued. "You can go in there for 20 minutes, 10 minutes, and feel a little bit of a difference."

The edge, then, as players describe it, isn't necessarily in the relaxation experienced while in the tank. It's that those moments of relaxation lead to better sleep later on. Improved quality of sleep is a very good thing for an athlete, of course, since it's linked to improved reaction time, quicker physical recovery, and an increased capacity for learning.

'IT'S STILL WEIRD TO ME'

Not everyone in the Patriots locker room is interested in floating. There are Patriots who have never dipped their toes in the tanks. Malcolm Butler hasn't tried it. Neither has Danny Amendola. They have their own routines that work for them, and they don't feel the need to stray.

Even for some who use it regularly, there are hurdles to overcome because for them it's just a little, well, strange.

"It's still weird to me," said rookie quarterback Jacoby Brissett, who has used the tanks to help him adjust to the long days that come with life as a professional.

"I've been in it a couple times, but it's still weird to me. It's definitely different. I'd never heard of it until I got here, and at first, I was like, 'What if I want to get out? Or what if I get locked in?' But you forget about it eventually."

Slater isn't claustrophobic, and he was more than open to the benefits of floating after hearing about them from Bill Belichick, head strength and conditioning coach Moses Cabrera and nutritionist Ted Harper.

Still, his first experience sounded like it would have been enough to turn him off to the whole idea.

"It didn't go very well," Slater said. "I remember getting salt in my eyes because it gets hot in there with the lid closed, and I was sweating. I wiped my eyes, my eyes were burning. Had to get out. It took me a while to get comfortable in there and get used to the process, but it's been pretty smooth since then."

As it is for most. In fact, back at Gillette Stadium, in order to make the experience as comfortable as possible, players can customize their float by plugging in their iPhones to punch up whatever audio they'd like, and the sound filters through speakers installed in the tanks.

Hightower, for example, likes to play Drake or some slower hip-hop to mellow him out. Edelman likes to listen to tunes before he dozes off as well.

"I put in some music where I can barely hear it, where I really have to concentrate on not thinking about anything just to kind of hear it," Edelman said. "And once I start thinking about it or start hearing the music, that's when I usually doze off because you have to get so focused on hearing the faint music.

"That's been my routine. You go in there, you can think if you want, but I tend to try to turn it off and relax my mind, and allow my head to recover from not only physical but mental use."

'MODERN-DAY NFL, MAN'

Soon after Edelman scoffed at the idea of hopping into what looked like a flooded space ship to make his body feel better, he had a conversation with sports scientist Dr. John P. Sullivan, who worked with the Patriots.

Edelman wasn't sleeping well at night, and Sullivan thought he should give floating a shot.

"He was a huge fan of it," Edelman said. "I was very close with him. He was always about the sleep studies . . . He told me to start going in this thing, and it helped."

Edelman also wondered if the tanks might help with the overall health of his brain. From what information he'd been exposed to, he explained, he understood that better sleep not only led to faster recovery time for muscles and better quick-twitch reactions. It also might help a player's brain recover from injury.

"When you play a physical sport," he said, "there's a lot of studies with head trauma that the more sleep you get, the more you let your brain rest, the better it is for your head."

Edelman, who has spent his eight-year career making a living over the middle and at risk of high-speed collisions as a punt returner, admitted he couldn't be sure if he's helped his own brain by floating, "but I definitely feel more rested," he said. "And your brain recovers when it's sleeping."

The science of how the brain is impacted by floating is still relatively new. But there are those like neuropsychologist Justin Feinstein, who believe float tanks may be able to help individuals dealing with distress, including PTSD. Others, including retired Navy SEALs Jeff Nichols and Alex Oliver, have been encouraged by what they've seen from special forces operators who experienced traumatic brain injury and turned to float tanks.

As athletes like Brady, Steph Curry and Aly Raisman continue to be linked to floating, it may continue to gain popularity in the sports world, but the Patriots are already sold. Now, as they get ready to take on the Falcons, they're hoping that by laying down in shallow pools of salty water they've in some small way put themselves in position to finish as the last team standing.

"Modern-day NFL, man," Slater said, shaking his head.